Supply constraints drive home prices in Canada

One of the most intriguing features of the pandemic is the relentless rise in Canadian housing prices. However, COVID has merely amplified a persistent long-term trend. In housing markets in Canada over the last two decades, we’ve seen a sustained increase in prices particularly in larger urban centres such as Vancouver and Toronto.

Between 2005 and 2020, the annual average of the Canadian Real Estate Association’s monthly Seasonally Adjusted Composite MLS House Price in Canada has gone from $255,625 to $609,892. And in April 2021, the average Canadian price hit $723,500. Single-family homes in Greater Vancouver now average just below $2 million and significantly more than $1 million in the Greater Toronto Area. Moreover, the price rise has spilled over into smaller centres across the country.

Simply put, the Canadian housing market appears to have gone bonkers and is causing a massive redistribution of wealth where existing homeowners benefit while future homeowners are left out. The Bank of Canada appears powerless to affect the situation via higher interest rates given the preoccupation with keeping rates low to not harm the post-pandemic economic recovery. Meanwhile, the federal government is trying to solve the problem via incremental steps. For example, as a demand-side policy, Canada’s banking regulator tightened qualification rules for uninsured mortgages to reduce their size. Of course, that will probably do little to prevent existing homeowners from tapping into their homes wealth via reverse mortgages to assist their children in buying homes, thereby continuing to inflate prices.

In the end, it’s all about supply and demand. Short-term solutions by governments have invariably been demand-side oriented (foreign buyer taxes, tightening mortgage qualifications, etc.). Little has been done to address the supply side because governments focus on the short-term rather than the long-term, which is where the supply side problem lies. However, it’s a conjunction of long-term demand and supply factors that have led to the current situation.

On the demand side, Canada’s population and population growth has gradually increased over the last 50 years, from 22 million to 38 million. Whereas the 1970s saw population increase by about 280,000 people annually, increases in immigration have helped generate annual average increases of 360,000 people per year since 2000. Indeed, 2019 alone saw an increase of Canada’s population by about 528,000. Meanwhile, household size has dropped from an average of 3.5 according to the 1971 Census to about 2.5 in 2016. There are more people seeking accommodation, and for smaller household units.

Now add a long-term decline in mortgage interest rates, which have fallen from double digit highs in the early 1980s to the present low single digits. Then add a doubling of per-capita incomes from 1971 to the present, and as a short-term demand-side coup de grâce, the country is awash in government fiscal support via CERB payments, extended employment benefits, child benefits and other support payments, which have added $180 billion to Canadian savings in 2020, some of which has gone into the housing market.

On the supply side, the housing supply has been unable to keep pace with increases in demand. Over the years, the supply of new housing has become more constrained due to the regulation of residential development. Some of these regulatory factors include land-use regulation with its approval timelines, timeline uncertainty, municipal council and community impacts, costs and fees, and the prevalence of rezoning. In the GTA, the Green Belt policies designed to combat urban sprawl have been blamed for rising housing costs with at least one estimate that the “sprawl-busting policies are responsible for a quarter to a third of the run-up in real-estate prices across the region.”

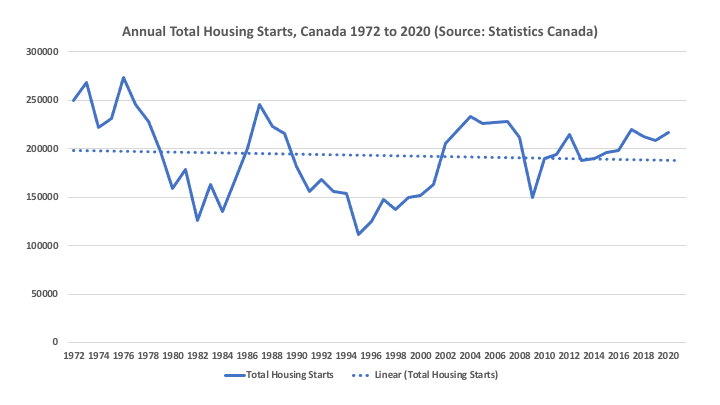

As a result, annual total housing starts (single detached and multiple units including apartments and condos) have essentially declined over the decades.

We’ve been adding less than 200,000 new housing unit annually (on average). This at a time of population growth, rising incomes, shrinking household sizes and declining interest rates. Again, housing supply has not kept pace with housing demand. While there’s been an uptick in housing starts over the 10 years, it’s dominated by condos while much of the rising demand is for single detached homes.

The housing market in Canada has become a sealed pressure cooker where the heating element has been on high for a while. Simply turning down the heat a bit won’t solve the problem. You must either turn the heat off completely—with catastrophic results to home values—or get a bigger pot. That’s easier said than done.

Author:

Subscribe to the Fraser Institute

Get the latest news from the Fraser Institute on the latest research studies, news and events.