Bank of Canada must stay aggressive to tame inflation

As expected, the Bank of Canada on Wednesday raised its target for the overnight rate by 50 basis points to 3.75 per cent as it continues efforts to bring Canada’s inflation rate under control.

This brings the number of increases this year to six, though this increase was not as high as some expected given the anticipated 75 basis points increase by the U.S. Federal Reserve that may come in November. As noted in the Bank of Canada news release, inflation is indeed a global phenomenon that remains high and broadly based and affected by global supply chain issues, high commodity prices, tight labour markets and the increasing strength of the U.S. dollar, which for Canada (which imports much from the United States) is also an important factor.

While inflation in Canada has slowed slightly, it remains high especially for items such as food and it’s expected that the Bank will continue to increase rates, which will remain high for much of 2023.

While inflation is exacting a toll on Canadians, higher rates are also affecting borrowing costs for many households with mortgages and there are increased calls for the Bank to pause the increases. Unfortunately, rates are must go higher rather than lower if we hope to bring inflation under control because fiscal policy is operating at cross purposes with monetary policy.

While the pandemic saw a combination of stimulatory fiscal and monetary policy, we are now seeing more restrictive monetary policy to combat inflation, but the federal government has increased spending considerably. Indeed, from 2019 to 2022, federal spending has grown an average of 9 per cent annually. When combined with structural changes in the labour market, inflation has become a much tougher nut to crack using monetary policy alone.

Why is this a problem?

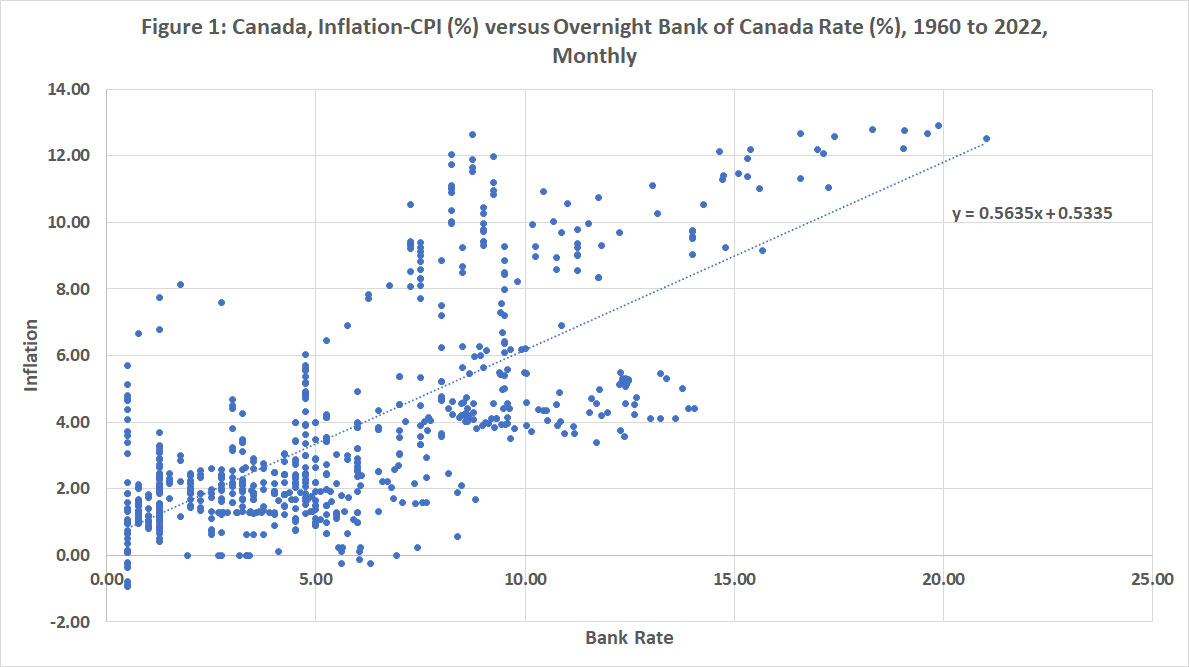

Using data obtained from the Federal Reserve Bank of St. Louis (FRED), the chart below plots Canada’s inflation rate against the overnight Bank of Canada rate monthly from 1960 to 2022 along with a linear trend.

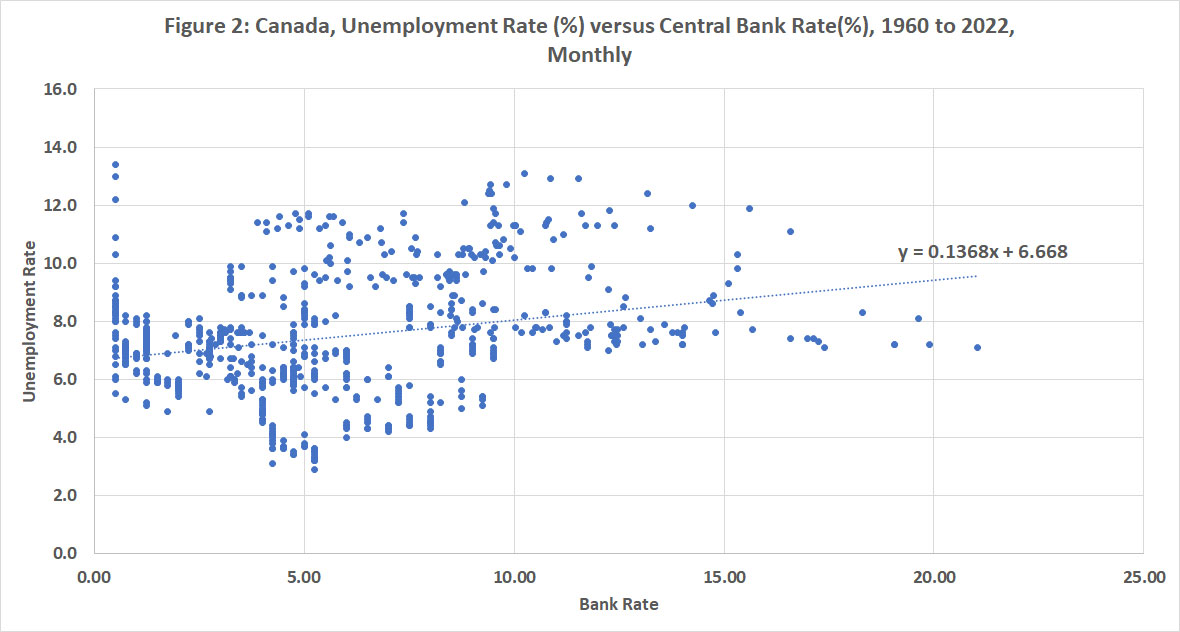

Based on that linear trend, a bank rate of 3.75 per cent is historically associated (on average) with an inflation rate of about 2.7 per cent. Using the same data source, the second chart plots Canada’s unemployment rate against the overnight Bank of Canada rate over the same time span and again with a linear trend.

Based on that trend line, on average a bank rate of 3.75 per cent was historically associated with an unemployment rate of 7.2 per cent. At present we have a bank rate of 3.75 per cent in conjunction with an overall inflation rate of close to 7 per cent and an unemployment rate of about 5 per cent. In other words, the unemployment rate is lower than one might expect, and the inflation rate higher given the interest rate based on the average historical relationship. This suggests the economy is still overheating.

The Bank of Canada must increase rates more than it has to-date because there are two forces affecting the longer-term relationship between interest rate changes and economic activity.

First, there’s the continuing federal spending stimulus in the economy. While the deficit-to-GDP ratio is coming down, the federal government is spending nearly one-third more than it was in 2019 before the pandemic.

Second, despite fears of technological unemployment and economic stagnation, an aging population and declines in some participation rates were making the labour market much tighter even before the effects of COVID. Unlike the 1970s, which saw a robust labour supply in the face of restrictive monetary policy given the relatively younger Canadian population and increased female labour force participation, today is characterized by labour shortages.

It’s not that restrictive monetary cannot work to bring inflation under control, but given the labour force changes in the economy and in the absence of federal restraint, there must be more increases and a much higher interest rate than anticipated.