Canada needs meaningful tax reform to compete with U.S. in oil and gas

With Canada’s beleaguered oil and gas industry facing challenges to export to other countries, one might think that governments would focus on some controllable levers to support the industry including taxation, which can have a significant impact on the competitiveness of the industry.

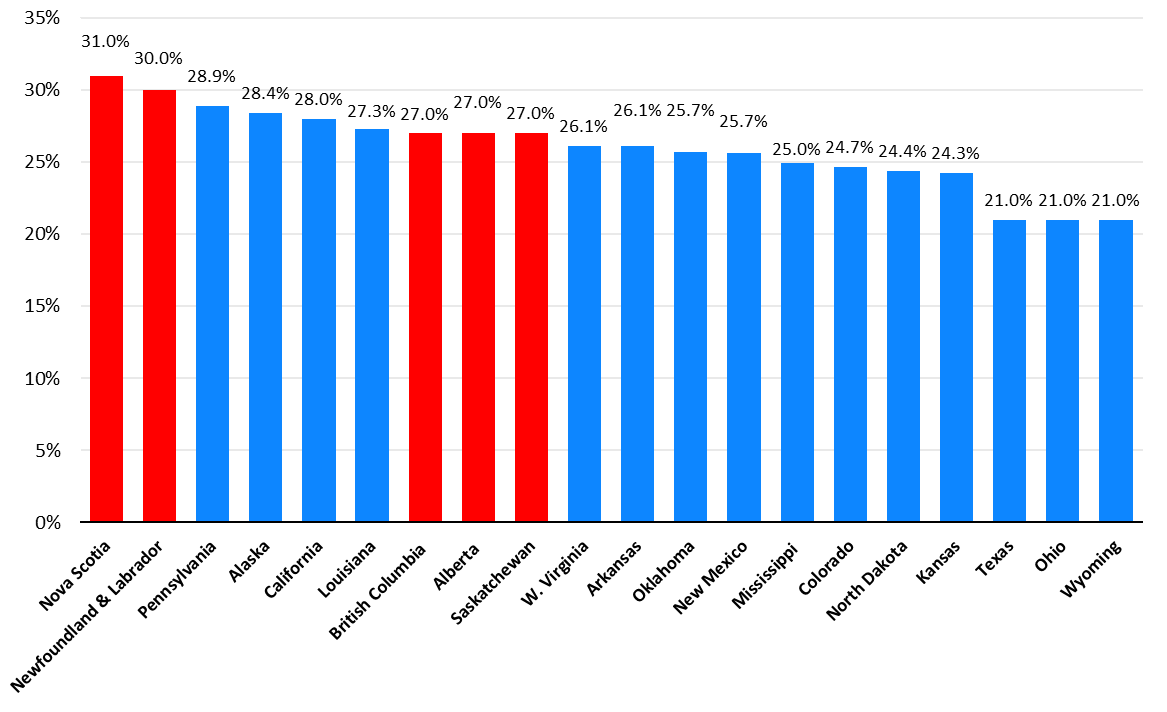

The United States in January 2018 undertook substantial corporate tax reform and made all industries more competitive. The federal corporate income tax rate dropped like a stone by 14 points to 21 per cent with some modest reduction generally at the state level. The U.S. also provides a concessionary tax rate of 13.125 per cent on marketing, intellectual property, service and certain other “intangible income” that now draws profits and certain related activities to the U.S. On top of it, U.S. companies can bring money back home without paying U.S. tax, which provides opportunities to reduce debt and other costs in the country now that the government is putting new limitations on various deductions. These actions ultimately erode the corporate tax base in Canada.

Canada’s response to U.S. reform was to introduce accelerated depreciation in November 2018. In an attempt to mimic the U.S. bonus depreciation in place for more than a decade (now 100 per cent write-off for next five years in the U.S.), Canada bumped up depreciation deductions for most investment expenditures on a temporary basis. No change was made to Canada’s federal corporate tax rate nor to other provisions to counter potential corporate base erosion as profits flee to the U.S.

So how do things stack up for the oil and gas industry after the U.S. dramatic tax reform and Canada’s less-than-dramatic response?

In a recent study for the Fraser Institute on effective tax and royalty rates after U.S. and Canadian tax reform, we find a mix of results. Taking into account corporate income taxes, sales taxes on capital purchases, capital taxes and resource levies, Saskatchewan now has highest tax and royalty burden on oil at 35.9 per cent. Its corporate income tax rate, recently bumped back to 27 per cent, combined with the federal rate, is more than several leading U.S. producing states including Texas at 21 per cent and North Dakota at 24.4 per cent. Saskatchewan also hits hard oil producers with a special resource levy on capital assets and retail sales taxes on many capital purchases.

British Columbia also fairs poorly compared to most U.S. states and provinces with a tax and royalty burden 31.9 per cent on natural gas, fifth highest of 18 provinces and states. Again, retail sales taxes on capital purchases are one major culprit.

Despite Alberta’s corporate income tax rate of 27 per cent being higher than many important U.S. oil and gas producing states, its overall tax burden is generally lower with the absence of a retail sales tax and lighter resource levies. In the case of oil, Alberta’s tax burden on investment is 23 per cent (21.3 per cent for the oilsands), well below the U.S. average of 28.6 per cent.

This good news, though, must be treated with caution. Canada’s tinkering with tax depreciation is woefully inadequate in many ways. For companies invested in Alberta and Texas, it makes sense to put profits down south and financing and general administrative costs into Alberta. The higher corporate tax rate in Alberta makes it appealing to move sales forces and IP licences to the U.S. To counter U.S. reform, much had to be done. In five years, accelerated deprecation will begin to be phased out anyway.

Besides, Canada is loading up the oil and gas sector with carbon taxes, overbearing regulatory processes (see Bill C-69) and transportation bans. If anything, a corporate tax advantage is needed just to make up for the considerable barriers to investment arising from other policies.

The smart policy for Canada would have been to undertake a larger reform of corporate taxation in Canada. To counter the loss of profits and investment to the U.S., federal and provincial governments should reduce corporate tax rates sharply accompanied with other policies to protect Canada’s corporate tax base. This has been the approach now adopted in 12 countries in recent years.

In Alberta, UCP Leader Jason Kenney, expected to win the next provincial election, promises to eliminate the carbon tax and cut the Alberta corporate income tax rate from 12 to 8 per cent in the next four years bringing some welcome relief to Alberta businesses. It might be the first step to create a more competitive environment for oil and gas. Much more is needed, however, especially laying down a few pipelines.

At least, Canada does not hammer oil and gas with high tax burdens (except in Saskatchewan and B.C.). That’s at least some solace for a challenged industry.

Combined federal and sub-national corporate income tax rates by major producing oil and gas jurisdictions in North America as of 2018