On the minimum wage, Ford once again follows Wynne’s lead

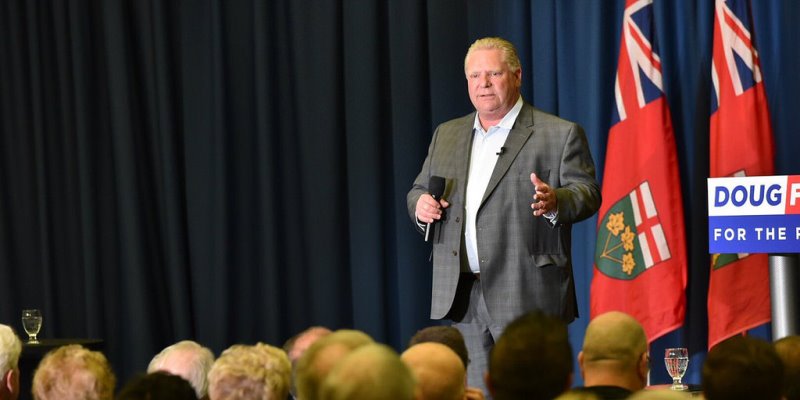

Despite sharply different rhetorical styles, Premier Doug Ford’s approach to several areas of public policy has been nearly indistinguishable from that of his predecessors, premiers Wynne and McGuinty.

In the latest example, Premier Ford recently announced that his government will increase the minimum wage from $14.35 to $15 in January. More on that in a moment.

Ford also campaigned on a promise to reduce spending and quickly eliminate the budget deficit, yet his pre-COVID approach to spending and deficit-reduction was nearly identical to the approach of his Liberal predecessors. In both cases, the government continued to increase nominal spending, albeit slowly, while hoping for revenue to shrink the deficit over time. And in both instances the result was continued deficits. Again, the Ford government’s resumption of the spending trajectory of the 2010s (by Wynne and McGuinty) was a far cry from what he promised on the campaign trail and represents an important policy area of policy continuity rather than change.

Tax policy is another area of similarity. Despite promises to make Ontario “open for business,” the Ford government maintained the Wynne government’s general corporate income tax rate, even though it’s one of the most economically harmful components of our tax mix. The Ford government also held the same top marginal personal income tax rate as its predecessors, which, combined with the federal rate, remains at 53.53 per cent.

Which takes us back to Ford’s recent promise to raise the minimum wage. On the campaign trail in 2018, then-premier Wynne promised an immediate increase in the minimum wage from $14 to $15 per hour. Then-candidate Ford offered a slightly different plan, committing to a $15 minimum wage but proposing to move there gradually to give businesses time to adjust.

Now even this minor policy difference has disappeared. According to Ford’s new plan, the government will not gradually implement the minimum wage increase but will simply enact a $15 wage floor in January. Yet again, the Ford government has pulled a page from its predecessor’s playbook.

And what about the minimum wage hike? Is it a good idea?

In fact, it comes with potential negative unintended consequences. For example, it will likely dampen job creation over time. A recent meta-analysis of minimum wage research found that a “clear preponderance” of evidence shows that minimum wages create disemployment effects, with the evidence clearer for teens, young adults and people with little education. While the effects of higher minimum wages on employment are different—depending on the time, place and economic conditions—again the best available evidence shows we should be concerned about the effects on employment for young and less-educated workers.

Moreover, during her time as premier, when arguing for the minimum wage increase (that Premier Ford is now enacting), Kathleen Wynne said it was part of an anti-poverty strategy. But we should also be skeptical of this claim. A recent study showed that 92 per cent of minimum wage workers don’t live in low-income households. Rather, they are secondary income-earners in households that are not considered low-income according to Statistics Canada’s threshold.

This reality, combined with the fact that many low-income households don’t even include a fulltime worker, has led leading University of Toronto labour economist Morley Gunderson to say that higher minimum wages are “at best an exceedingly blunt tool for reducing poverty.”

Ontario’s minimum wage now joins government spending, deficit-reduction and tax policy as policy topics where it’s difficult to distinguish between the Ford government and its predecessors. Despite sharp differences in their communications style, in many important areas the Ford government has continued the approach of its predecessors rather than charting a new course of its own.