Three ‘hard truths’ about Canada’s trade

Canada is an “open” economy that depends on cross-border flows of trade, investment and data/knowledge to maintain high living standards. To pay our way in a very competitive world, Canadians must produce and sell goods and services to customers in other countries. These exports furnish the means to pay for the vast array of imports that contribute to the well-being of Canadian households and allow our businesses to operate efficiently and grow by accessing bigger markets.

In 2022, Canada exported $779 billion of goods to other countries, along with $161 billion of services, for a total of $940 billion. The services category includes a wide array of commercial services including professional, scientific, technical, digital and financial, as well as transportation services and international tourism (when non-Canadian visitors travel to spend money here).

About three-quarters of Canada’s exports are destined for a single market—the United States, whose economy has steadily expanded in size over time to reach some US$25 trillion of gross domestic product today. Canada also sources the bulk of our imports from the U.S.

The centrality of the American market to Canada’s economic prosperity is the first “hard truth” about Canada’s trade, a point explored in a recent paper by Steve Globerman. Despite periodic efforts to diversify Canada’s trade and commercial links over the last 50 years, Canada remains as closely tied to the American economy today as we were in the 1990s. There’s little reason to believe the Trudeau government’s recently unveiled “Indo-Pacific” strategy will change the situation. Proximity, a common language and business culture, and the impact of extensive and unusually deep business and personal ties all serve to reinforce the American-centric character of Canada’s trade. It follows that the U.S. should continue to figure prominently in the trade promotion and investment attraction activities of Canadian governments.

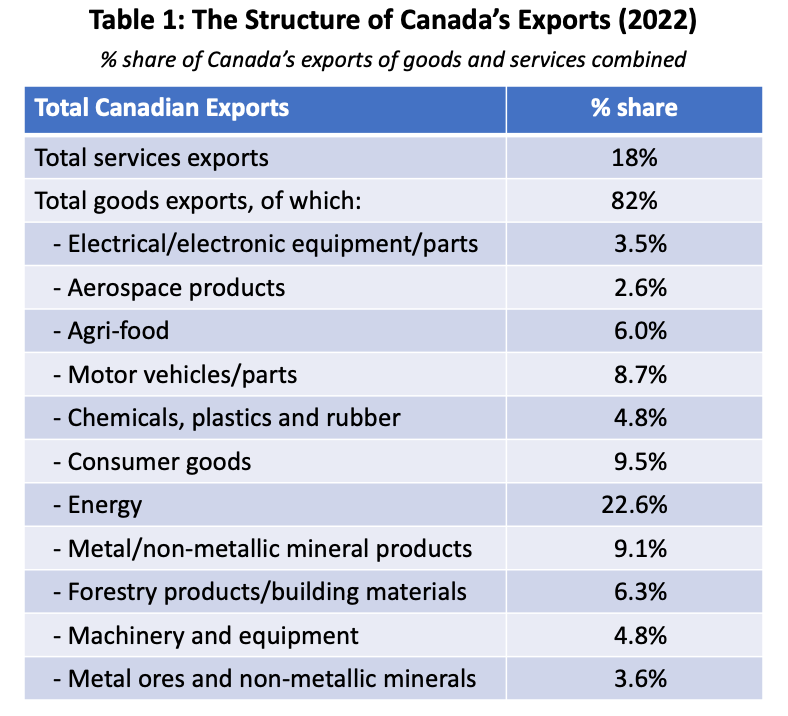

A second “hard truth” about Canada’s trade is the outsized place of natural resource-based products in the export mix. The first table below breaks down Canada’s goods and services exports in 2022 into the main groupings.

Added together, energy, non-metallic minerals and related products, metal ores, forest products and agri-food comprise almost half of the country’s total international exports of goods and services combined. Energy alone supplied 27 per cent of Canada’s merchandise exports (and 23 per cent of total exports) last year, generating a remarkable $212 billion in export-driven income for Canadian businesses, workers and governments.

Within the energy basket, oil and oil-based products dominate, providing about three-quarters of energy-based export revenues. Contrary to innumerable speeches and press releases issued by the current federal government, the energy share is likely to rise in the next several years, as LNG production from British Columbia comes on-line and Western Canadian oil exports increase following the completion of pipeline expansion projects.

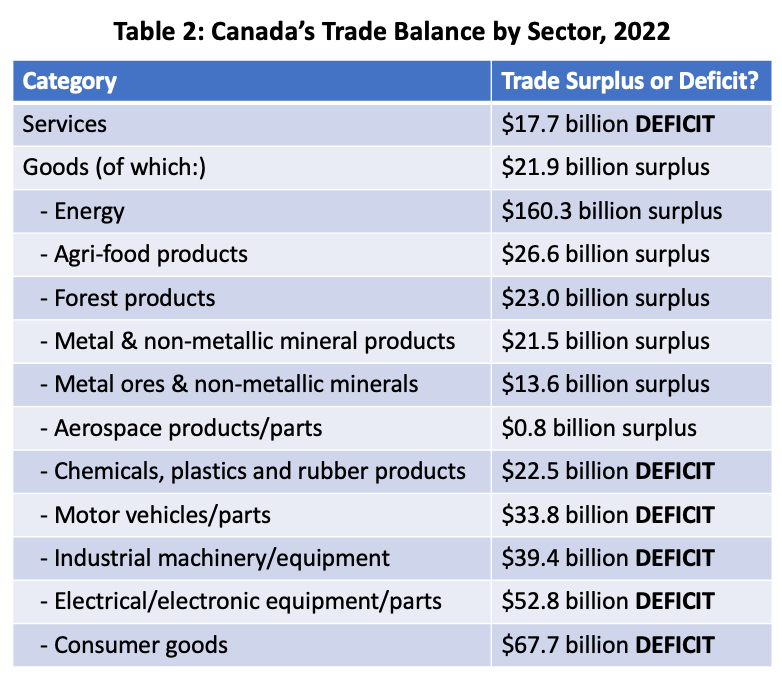

The final “hard truth” is closely related to the second but carries a more nuanced message. Ultimately, every country will have a ledger showing the trade surpluses and trade deficits across its various industries. In Canada’s case, a small number of sectors reliably generate significant trade surpluses, which help finance large trade deficits incurred in other parts of our economy.

The second table provides a snapshot of Canada’s trade “balances”—the mix of deficits and surpluses by broad industry category.

The story is a fairly simple one; positive trade balances in the energy, mining, forestry and agri-food sectors offset chronic—and in some cases very sizable—trade deficits in consumer goods, chemicals and plastics, motor vehicles/parts, and industrial and electronic goods. We also run a smallish deficit in our overall services trade.

The trade data are informative. Among other things, they tell us where Canada has, in the language of economists, a “comparative advantage” in the global context. For a market-based economy, a pattern of positive trade balances is evidence that it very likely enjoys a comparative advantage in the industries which report consistent trade surpluses. Armed with such information, smart policymakers should strive to create and sustain an attractive business and investment climate for the industries that produce trade surpluses. Unfortunately, this is a lesson that today’s federal government in distant Ottawa has struggled to digest.

Author:

Subscribe to the Fraser Institute

Get the latest news from the Fraser Institute on the latest research studies, news and events.